Bacterial biofilms: why should we care?

The impact of biofilms on animal health and public health is undeniable. I am spending part of my sabbatical leave here at CReSA working on a collaborative project with Virginia Aragón on biofilm formation by Haemophilus parasuis, another important swine pathogen.

What are biofilms?

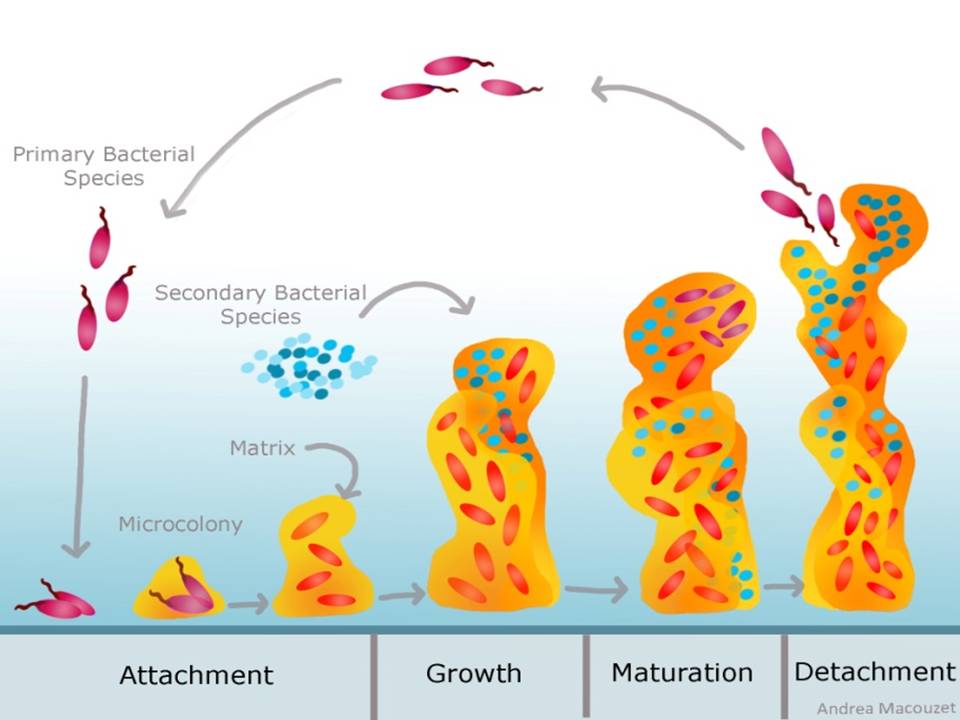

Bacterial biofilms are generally defined as structured clusters of bacterial cells enclosed in a self-produced polymer matrix that are attached to a surface. Bacteria can adhere to cells and tissues as well as to solid surfaces (e.g. floor or equipment found at a farm, slaughterhouse, or processing plant).

It is estimated that 80% of the earth’s microbial biomass resides within biofilms. Biofilms appear to facilitate the survival of bacterial pathogens in their environment and their host. Bacterial biofilm isolated from a wide range of niches share several common characteristics: (1) bacterial cells are enclosed in polymer matrix composed of exopolysaccharides, proteins and nucleic acid; (2) biofilm formation is initiated by extracellular signals present in the environment or produced by the bacteria; (3) the biofilm protects bacteria against the host immune response, desiccation and biocides (e.g. antibiotics or disinfectants). The latter characteristic is of course of great importance in human and veterinary medicine.

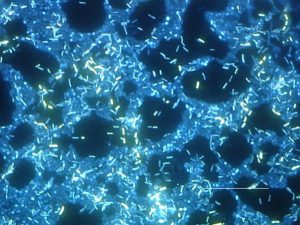

Despite extensive scientific coverage of biofilms associated with human infections or industrial processes, biofilm formation by bacteria of veterinary importance and associated with zoonotic diseases have received very little attention. My laboratory is studying biofilm formation by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, an important respiratory tract pathogen of swine, and by coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from bovine mastitis. We have developed or adapted in vitro models to study biofilms under static conditions or in the presence of a liquid flow. We use screening of library mutants and determination of genes expression to know more on the genes that are important for biofilm formation and dispersion. We also rely greatly on confocal microscopy to visualize and characterize the biofilms.

I am spending part of my sabbatical leave here at CReSA working on a collaborative project with Virginia Aragon on biofilm formation by Haemophilus parasuis, another important swine pathogen. The project was initiated three years ago when one of my graduate students, Vincent Deslandes, came to CReSA for several months through a financial support of the Gouvernement du Québec. We observed a marked difference between virulent and non-virulent strains of H. parasuis in their ability to form biofilms.

So, why should we care?

Because the impact of biofilms on animal health and public health is undeniable. Biofilm formation can increase the resistance of bacteria to antibiotics, disinfectants and host immune response. Therefore, biofilm formation can interfere with the proper treatment of animals or effective disinfection at the farm, the slaughterhouse or the processing plant. It is also important to keep in mind that biofilm formation is not restricted to animal pathogens and animal infections, several food-borne pathogens, including Listeria, Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella have the ability to form biofilms. Research aimed at developing strategies to prevent and treat infections of animals must take into consideration the unique characteristics of biofilms. Further research is also required to develop effective disinfection protocols to eliminate biofilms from the farm and food-processing environments, because biofilms can act as a reservoir for infectious agents.

Article reference:

Jacques, M., Aragon, V., & Tremblay, Y. D. (2010). Biofilm formation in bacterial pathogens of veterinary importance. Animal health research reviews, 11(2), 97-121. DOI: 10.1017/S1466252310000149

Contact:

Mario Jacques

Professeur de microbiologie

Faculté de médecine vétérinaire

Université de Montréal

St-Hyacinthe, Québec, Canada

mario.jacques@umontreal.ca